Guest Blogger Ian McMillan writes: Week 8 was about levels. Scraping back the (apparently) flat site to incorporate foundations, pads, ground slab and domestic drainage. Given that the site is only 250m2, the 260 cubic metres/ 130 tonnes that has to be removed off site does seem incredible.

Guest Blogger Ian McMillan writes: Week 8 was about levels. Scraping back the (apparently) flat site to incorporate foundations, pads, ground slab and domestic drainage. Given that the site is only 250m2, the 260 cubic metres/ 130 tonnes that has to be removed off site does seem incredible.

However the levels are the key to the design.

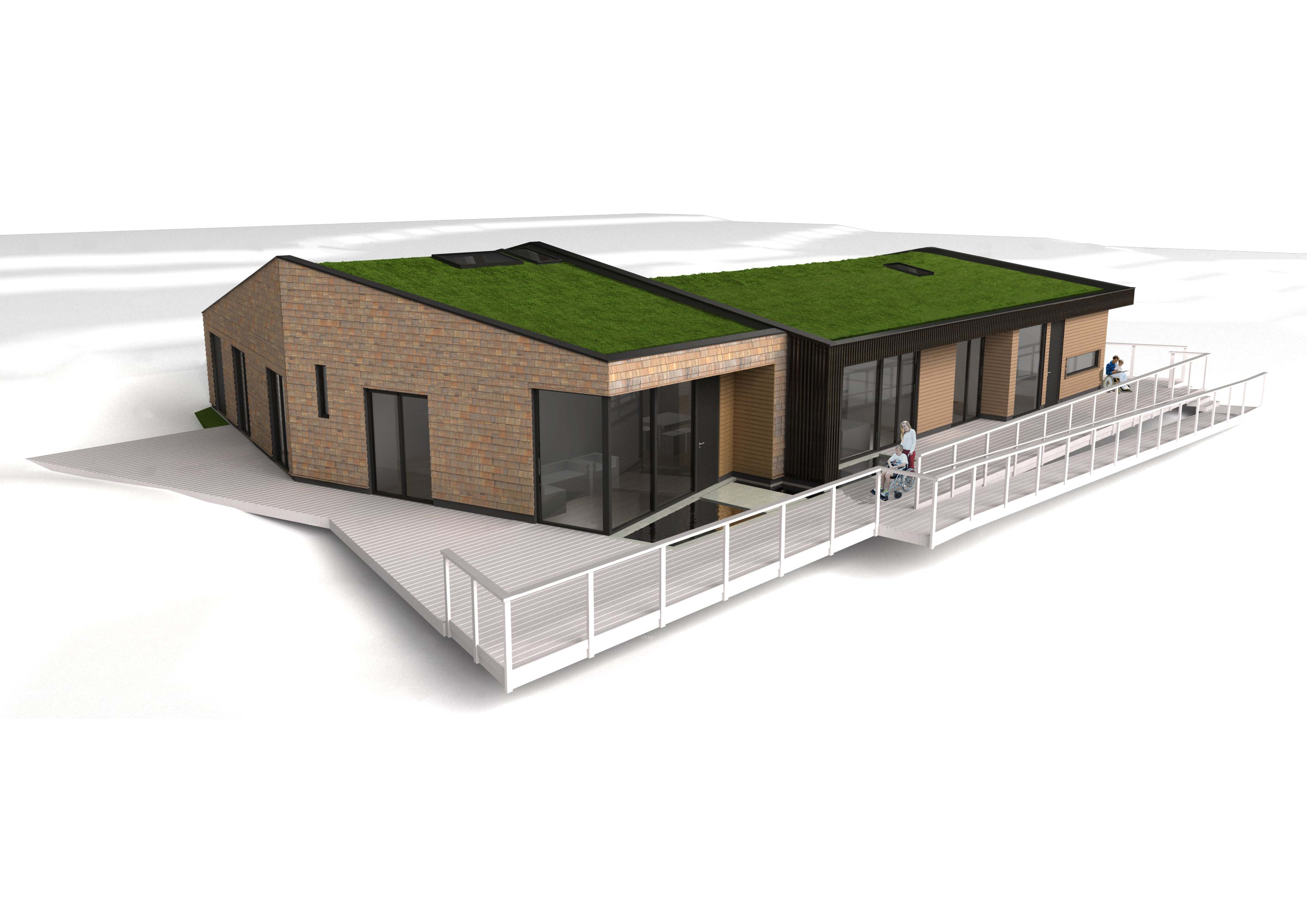

With the house design, rather than 2 levels with a ramp ‘bolted on’, we had looked at various early C20 European architects, particularly Adolph Loos, and how they arranged spaces and events around the circulation to create a journey through the space. This not only breaks down the (apparent) ramp/ circulation length, but also converts it into a usable space.

We looked at various ramp configurations, but the ‘Z’ formation gave the longest length within the site confines, but also suited the spatial demand and program. This curiously formed more solid edge of smaller ancillary spaces to the street, and opened up the larger living spaces onto the garden. We had originally hoped for a 1:10 ramp, but mainly as this was a round number, however in reality this developed into a 1:9 gradient. We were uncertain of this gradient primarily as we are used to working within the building standards of 1:20, 1;15 and 1:12, and all with their incredibly short flight lengths, however where did these figures come from and why? From our European travels we have seen countless example of ramps within public buildings which are steeper, and importantly practical and manageable. Recently in London we were in the Turbine Hall of the Tate, and measured the 80m long single flight ramp at 1:12. Those non-compliant European architects! In reality we navigate these gradients in the everyday in Edinburgh, where most of the streets in the Newtown are sloping at between 1:12 and 1:8.

The City of Edinburgh Council were concerned about our proposal, and asked us to demonstrate why we thought the ramp was practical, and how we could future proof the design by the provision of a lift space. It was eventually accepted albeit reluctantly.

It went as follows:

The report follows on from a meeting with The City of Edinburgh Council on 8 October 2011, where the following two key points were raised:

1 – Is there future and spatial provision for a lift within the house?

2 – Is the ramp an acceptable gradient?

Introduction

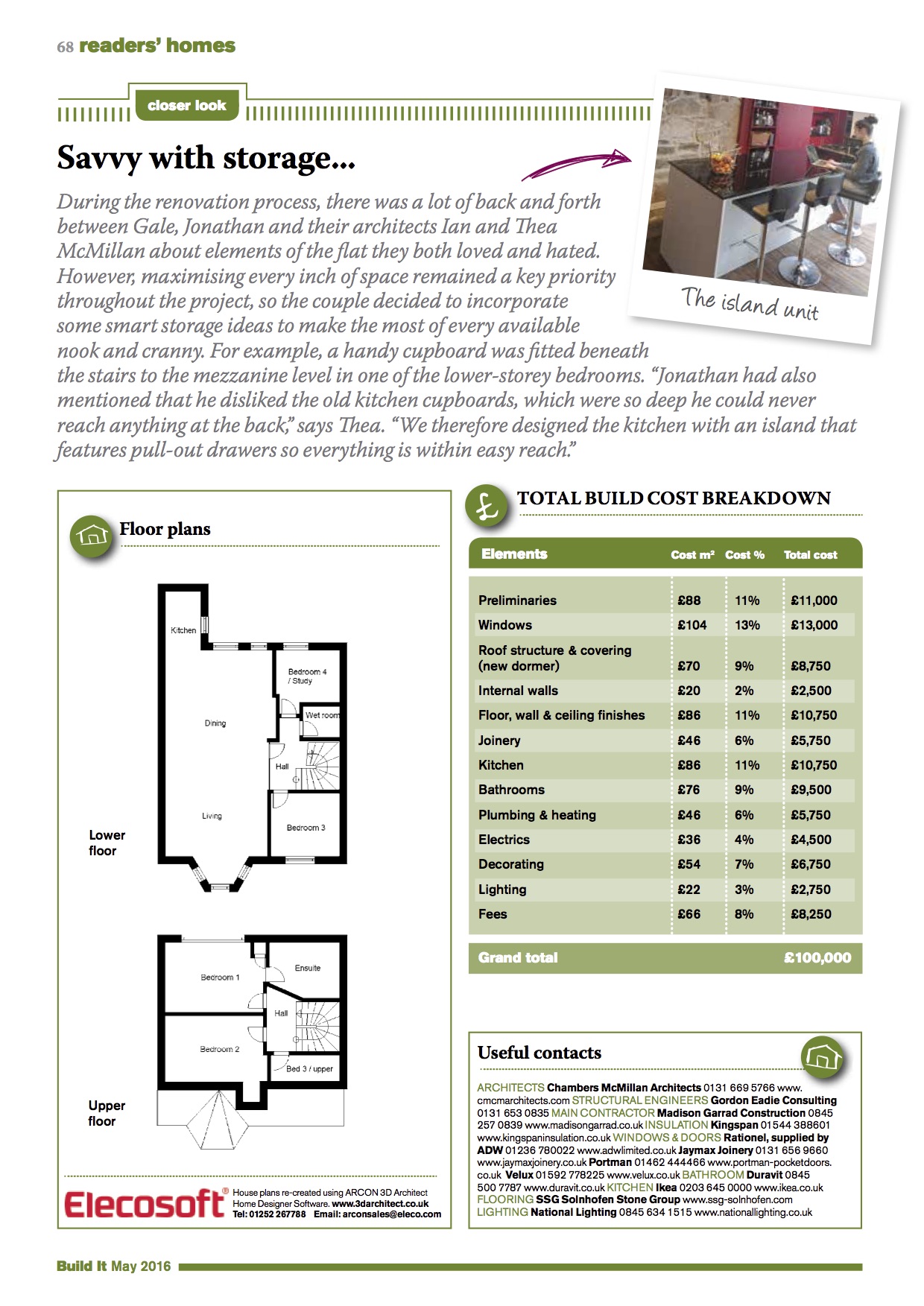

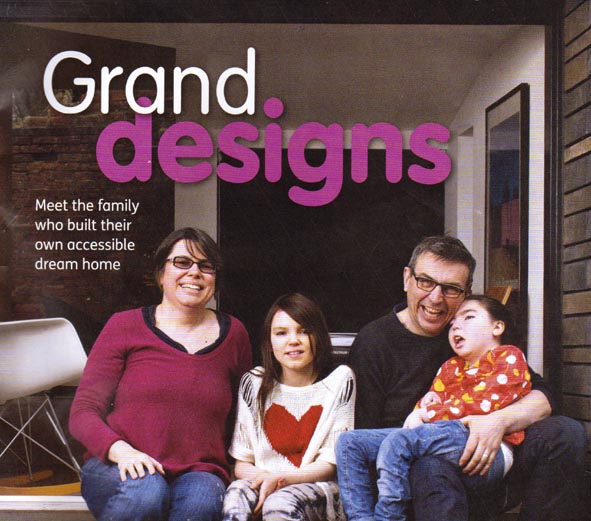

We are designing and building a home for our daughter who is a wheelchair user. The intention has been that it should be fully accessible and barrier free and allow Greta to take part in all of our everyday activities. The house should also be as adaptable and as future proof as possible.

As we are both architects we wrote the brief of all the spatial and user requirements and designed the house from the inside out. We also took advice and design development guidance from Tom Lister from People Friendly Design who is an accessibility consultant, and has cerebral palsy himself, and also contributes to policy on accessibility for the Scottish Government.

The site where the house itself is situated is in central Portobello, the community where we live. It was key that we continued to live in and around the people Greta knows and the school she attends.

In order to achieve the above, the design has incorporated a ramp to connect the levels. This is important for a few key reasons:

1 – No reliance on mechanical equipment. Although the ramp does take up space within the house, the non reliance on mechanical equipment is a great benefit, and make the house more ‘normal’.

2 – Cognitive development. Research shows that movements through spaces allows a greater understanding of them

3 – Connectivity. The ramp has been designed in sections which breaks up its length and connects spaces along its route. This makes it more integrated and purposeful.

Other key features that the house offers are:

- Accessible car port

- Barrier free threshold

- Accessible kitchen work surfaces

- Direct access to the garden

- Snoozlum space

- Physiotherapy space

- Steel fames to allow for future hoisting if required

- Steel frame and space for future lift if required

- Accessible wet room and WC

- Good visual connections between spaces

Future lift provision.

Although we designed the building to function without the provision of a lift we have considered the possibility of requiring one in the future. The building has a steel frame which allows it flexibility within its layout and plan. There are two possible and practical locations for a lift to be incorporated the design.

Option 1

The lift would be located at the bottom of the existing stair as shown. This would give direct access onto the first floor landing outside the bathroom. The staircase is easily removed from the surrounding steel frame and would be reconfigured to either come up from the small living space adjacent to the kitchen, otherwise the main ramp itself could be used. The main ramp could be also easily converted into a stepped ramp if required. Flat timber treads could be added over the ramped surface and these would be 1.2m long and the step rise would be 150mm. This would be an acceptable and compliant stair within the technical handbook (Scottish building standards)

Option 2 – This would enter the lift from the small living space adjacent to the kitchen as shown, and it would exit on the upper level outside the bedroom but within the circulation area. Again the main stair could be reconfigured within the space but be a more spiral like design, or the ramp could either be used or adapted.

Proposed ramp design.

The ramp within the house is deemed non-compliant in terms of the Scottish Building Standards. We were unable to design in a compliant solution due to the building plot not being large enough. The proposal does make the ramp length as long as possible and has been designed to break the ramp into small sections.

Although it is technically non compliant we believe it is in the spirit of the design guidance.

Ramps are not normally incorporated within domestic buildings primarily as they take up more space than stairs of a lift, but are often incorporated within public buildings. Scottish building standards have to therefore write the guidelines specifically for public usage of ramps where they have to be able to cater for all abilities, rather than the specific individual. They also make no distinction between an internal and external ramp although the external ramps have to deal with rain, wind and snow which will require them to be shallow.

Therefore the guidelines deem any gradient greater than 1:20 to be a ramp. They suggest that the ramp is broken into sections to assist the ambulant disabled to have flattened pausing spaces. This is covered under the building standards.

Scottish Buildings standards

Building standards suggest that a ramp up to 1:12 gradient is acceptable in terms of safety for public usage within public buildings. Gradients of more than 1:12 are considered too steep to negotiate safely and are not recommended..

That said this is guidance only and is not legally enforceable.

Technical standards have accepted our proposal of 1:9 gradient as there is an alternative and compliant means to access the upper floor.

British Standards BS-8300

These are the guidelines from which the building regulations are based and from which the Technical standards reference, hence recommend the same ramp gradients..

Research on the subject does come up with some worldwide alternatives on the issue.

Neuferts New Metric handbook – This is a german publication and is the basic guideline to building design. They recommend that the steepest ramp gradient should be 1:8, and above that the walking pace of a pedestrian is slowed down.

Independent living

This is a UK website and asks what is the steepest gradient acceptable for a wheelchair ramp. They recognise that the ideal ramps gradient is 1:12, but this cannot always be accommodated. They suggest that the steepest practical gradient is 1:6, which is that of portable ramps.

ADA American Disability Association

This again verifies the above. The standard accessible ramps with the USA is recognised as 1:12 within all the states. This ramp can be an unbroken single flight up to 30 feet/ 9 metres. They suggest that shorter ramps can be used up to 1/6 gradient with the maximum steepness being 1:4 which is an unoccuoied chair being loaded into an accessible vehicle.

European examples

Looking at built examples within Europe we have used the book ‘housing for all ages’ again a german publication, which has drawings, specifications and photographs of ramps

This has a built domestic examples of 1:6 ramps without landings for wheelchair users.

Ramp Summary

The UK and US authorities will permit a 1:12 recommended gradient, with the US allowing much longer unbroken lengths. Both the UK and US will accept 1:6 as the maximum gradient. However Germany and other mainland European countries have many built examples of long unbroken wheelchair ramps within private residences of 1:6.

Conclusion

Our proposal lies within the middle of these ranges at 1:9. This figure came from the maximum practical length of ramp we could fit within the site. We then built a full scale model of this to verify our finding and to ensure that we were comfortable with this gradient and that we found it manageable. Europe has give us many built examples of accessible houses with much steeper wheelchair ramps of 1:6, with the UK and the US accepting these as permissible gradients but outwith any guidance and legislation. Ultimately the decision is up to the individual as it is within a private house and not within a public building. However if the ramps is above 1:12 the individual must satisfy themselves that they have considered the risks. We feel we have done this as:

1:9 is just outside the 1:12 recommendation

1:6 is an acceptable gradient for shorter sections within the UK and US

1:6 gradients have been successfully built within accessible houses in Europe.